Gerald L. K. Smith a Political Force

In the 1930s, with Americans struggling for survival in the worst economic disaster in their history, Smith addressed more and bigger live audiences than any speaker of his generation. They rarely left disappointed. With his beak-shaped nose and piercing blue eyes, standing six feet tall and weighing over two hundred pounds, he was a dynamo who swayed thousands and infuriated communists, new dealers, christ haters, and the Jew controlled media. His crisp voice, his spontaneous gestures, his transparent zealotry fixated audiences. Routinely, Smith was mesmerizing. His oratory impressed crowds, raised emotions, thrilled the masses. He was audacious and charismatic. Journalist William Bradford Huie wrote of Smith in the 1930s: “The man has the passion of Billy Sunday. He has the fire of Adolf Hitler. . . . He is the stuff of which Fuehrers are made.” “Before a live audience,” another journalist wrote, “he makes Father Coughlin seem somewhat less articulate than a waxworks.” He was, said Huey Long, “the only man I ever saw who is a better rabble-rouser than I am.” H. L. Mencken, who in his long journalistic career had listened to orators from William Jennings Bryan to Franklin Roosevelt, wrote: “Gerald L. K. Smith is the greatest orator of them all, not the greatest by an inch or a foot or a yard or a mile, but the greatest by at least two light years. He begins where the best leaves off.”

Gerald L. K. Smith's History

He was a son of Wisconsin, born and bred, where his parents’ families had moved in the 1850s and 1860s via western Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana after several generations of steady westward migration. His American roots on both sides of his family lay in the South — Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee — and went back to the 1600s. His ancestors included Quakers, Tories, a Civil War veteran, and virtually every strain of pre-Revolutionary Anglo-American. His father, Lyman Z. Smith, himself had been born in Wisconsin and Lyman’s father, Zachariah, in Ohio.

In 1855 Smith’s grandfather Zachariah moved from Indiana to Wisconsin. The Smiths were instrumental in founding the Sugar Grove Church of Christ. The congregation got going in 1855, and Zachariah later donated land for the present building. Some seventy years later his grandson Gerald began his ministerial career in a nearby Church of Christ in Soldiers Grove, and various cousins of Gerald have served in the ministry almost without a break ever since.

Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith came into the family on February 27, 1898, his parents’ second and last child. The family practiced devout Christianity, and church and household religious activities loomed large in Gerald’s life. Smith’s parents taught him that the Bible as the literal word of God, and Smith read the Bible repeatedly, cover to cover. He proudly remembered a proverb of his father’s: “If it is more than the Bible it is too much, if it is less than the Bible, it is not enough; if it is the same as the Bible we don’t need it.”

As was typical in rural Wisconsin around the turn of the last century, Smith’s formal education began in a spare, one-room schoolhouse without indoor plumbing. The school was about a mile northwest from the Smiths’ equally spartan four-room house in Richland County. By the time he was nine, Smith claimed to have memorized the lessons through grade eight. Smith said that he soon outgrew the rural school and persuaded his parents to let him attend the better schools in Viola, about seven miles north. He remained there through his freshman year. The Smiths moved to Viroqua, where the schools were larger and better, although they did not sell the farm.

Young Gerald seemed to have found in high school his future as an orator and speaker. His “Senior Superlative” in the annual called him “the most talkative.” As a newcomer to Viroqua in his sophomore year, he was elected class president. Along the way to graduation in 1915, he was president of the school’s literary society, business manager of the 1915 annual, “yell master” for the sports teams, Duke Orsino in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (the senior class play), a member of the track association in his junior year, a performer in the minstrel show, a soloist in the glee club, and a standout in oratory and debate. In oratory in his senior year, he took first place in the league contest at Sparta, delivering William Jennings Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” peroration “with the fire and eloquence of a Daniel Webster.” For his senior annual, he wrote essays about school spirit and a thirty-below-zero basketball excursion to Viola. In short, he was a high school success, and he graduated from the German-language sequence (the school offered several language-based courses of study) with a class of twenty-four on June 4, 1915.

In the fall of 1915 he entered college — Valparaiso University in Valparaiso, Indiana, then known as “the poor man’s Harvard.” Smith made his way by mowing lawns, washing dishes, waiting on tables, and serving a small congregation in nearby Deep River, Indiana. Valparaiso was basically a two-year, degree granting school, and Smith received a bachelor of oratory degree there in August 1917, having taken additional classes in religion.

In January 1918, when he was only nineteen, Smith accepted his first pastoral call, to the Soldiers Grove Church of Christ, a six-year old congregation with a brand new, cement-block church and a $2,500 debt. By June sixty-five new members had joined the church roll, and Bible school enrollment had more than doubled. In June the congregation invited a visiting minister from Illinois, George L. Snively, to its homecoming weekend, and he raised pledges of $4,100 “to liquidate the old debt, complete our basement and buy a new bell.” The delighted congregants took up collection to thank Smith and bought him a gold watch “as a reminder of their love and esteem for himself and his work.”

In January 1920, he accepted a pastorate at Footville, about ten miles west of Janesville. There, too, he quickly became a success with his preaching. “Bro. Smith preaches the gospel plainly week after week, but the people seem to delight to hear it,” so much so that within a year the small congregation had grown by 125 members. Articles about him and his work appeared regularly in the Disciples of Christ official publication, the Christian Standard. While at Footville, Smith met a strikingly attractive church singer from Janesville, Elna Sorenson, daughter of a middle-class, devout family. Elna and Gerald dated for a year and then were married on June 21, 1922. A quiet, modest, beautiful woman, Elna supported her husband in all of his political crusades, a true helpmate who made his priorities her own. Over the course of their fifty-two-year marriage, Elna Smith would give birth to their son Gerald, Jr. (Gerry), work the crowds at Smith’s speaking engagements no matter how many protestors were present, and serve as an associate editor of many of his publications.

By the time of his marriage, Gerald left Footville and became the pastor of a newly organized congregation in Beloit. While there he accepted a speaking engagement at the denomination’s national congress in St. Louis, he spoke about how to overcome difficulties in a rural church setting. The talk proved to the body’s national leaders that Smith possessed exceptional oratorical gifts, and thereafter his career took off. He then moved to a church in Kansas, Illinois, where he stayed a year; then in late 1923 he accepted a call to a church in one of the denomination’s most important strongholds in Indianapolis. He was only twenty-five. His ministry there abruptly ended in 1929 when Elna was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and doctors urged the couple to move away from the coal - infused air of the midwestern industrial city.

Although Smith considered offers to relocate in several locations, it was the discovery that Shreveport Louisiana had an excellent reputation for tubercular convalescence that made the choice clear. Smith’s original plan was to remain in Louisiana only for the amount of time Elna needed for a full recovery. He had no idea that this decision would land him in a place where his rhetorical skills would carry him from the pulpit to the national political lectern.

As before, he proved an effective pastor, adding new members and raising money. While trying to help several members who were facing foreclosures, Smith met the Louisiana politician Huey P. Long. As governor and then U.S. senator, Long was the most powerful politician in Louisiana’s history. Smith later said that the banker who wanted to foreclose was a Jew. His position on the Jews arose from his fervent Christianity which inclined him to view Jews as the enemies of Jesus.

Smith soon left the ministry which was brought about by his growing public association with Huey Long, and his support of the politician’s agenda that alienated the wealthy and conservative board members of Smith’s church. Seven months after arriving in Louisiana, Smith left his Shreveport church, and he never returned to the pulpit.

Huey Long offered him a job. Long was planning to challenge Franklin Roosevelt for the presidency in 1936. The focus of his appeal was a plan to redistribute some of the millionaires’ gross wealth to the improvised masses. It was a popular program to many in the depths of the Great Depression. Long’s approach was clever and strategic. Smith was to be its chief advocate, touring the nation to organize local units of the Share-Our-Wealth Society. (continue go to top)

Smith loved the work, and he thrilled rural audiences with his oratory. Farmers and merchants flocked to his speeches and joined clubs. He exhorted them to “pull down these huge piles of gold until there shall be a real job, not a little old sow-belly, black-eyed pea job but a real spending money, beefsteak and gravy, Chevrolet, Ford in the garage, new suit, Thomas Jefferson, Jesus Christ, red, white and blue job for every man.” Those who signed up for the local clubs received membership cards and became part of Huey Long’s growing mailing list, and by 1935 there was 27,000 clubs with a membership of 4,684,000 and a mailing list of over 7,500,000. Smith had a program: impeach all traitors including FDR, deport Jews and blacks, repeal the income tax, outlaw communism, and make America, capitalism, and Christianity synonymous.

President Roosevelt feared the national popularity of Huey Long. But the hopes of Long, Smith, and their millions of supporters crashed when Long was assassinated in September 1935. Long’s assassin was Dr. Carl Austin Weiss a racial Jew. Smith delivered Long’s funeral oration at the Louisiana capitol before 150,000 people. “This tragedy fires the souls of us who adored him,” he said. “He has been the wounded victim of the green goddess; to use the figure, he was the Stradivarius whose notes rose in competition with jealous drums, envious tomtoms. He was the unfinished symphony.”

Following Long’s death, Smith found a new ally in Dr. Francis E. Townsend of California. Townsend, like Long, had a panacea for the Depression. It was called the Townsend Recovery Plan. Smith, joining the board of directors, raising money, and organizing a youth corps. The Townsend-Smith alliance gained momentum. The movement needed Smith’s youth, vitality, and charismatic oratory.

Father Charles Coughlin was also on the scene. Coughlin was a formidable figure. A Catholic priest with a large congregation in suburban Detroit, he had the largest radio audience in the nation. More people listened to “the radio priest” than to Roosevelt or to “Amos ’n’ Andy.” Coughlin had broken with Roosevelt after initially supporting him. The priest thought Roosevelt was planning to drag America into WWII.

The 1936 presidential campaign brought together Smith, Townsend, and Coughlin in the Union Party. Their united following was enormous and fanatical, and Smith and Coughlin were the most eloquent public speakers in the nation. None of them was a credible candidate; Coughlin was a priest born abroad, Smith had no political experience, and Townsend was a septuagenarian. They therefore selected a candidate who seemed to be an amiable politician, William Lemke of North Dakota.

On July 15, 1936, the Union Party national convention was held in Cleveland. Smith spoke, and no one dozed, though he spoke for three hours. Brandishing a Bible, he said that if it was rabble-rousing to defend the Constitution, praise the flag, and advocate the Townsend Plan, he wanted to be the best rabble-rouser in the country: “You give me the Bible and the Constitution and the Flag and the Townsend Plan, and I will do ten thousand times as much as you will with the Russian primer, and the Lenin communistic Marx plan.” As H. L. Mencken reported, Smith’s speech “ran the keyboard from the softest sobs and gurgles to the most earsplitting whoops and howls, and when it was over, the 9,000 delegates simply lay back in their pews and yelled.”

Three weeks later, eight thousand Coughlin supporters gathered for Coughlin’s convention of the National Union for Social Justice. Townsend, Coughlin, Lemke, and Smith spoke, but it was Smith who stirred audiences most successfully. He told the Coughlinites, “I come to you 210 pounds of fighting Louisiana flesh, with the blood memory of Huey Long, who died for the poor people of this country, still hot in my eyes.”

The Union Party effort failed. It spent only $95,000 while the Republicans spent $14 million, and the Democrats, $9 million. They could only do little grassroots organizing. They made no overtures to organized labor. Roosevelt’s New Deal had worked no miracles, and the economy had not improved even though they kept espousing a propaganda of hope. Voters believed the FDR fiction of hope could deliver while the Union Party's plan could not, so the depression continued.

Gerald L. K. Smith’s audiences may have peaked with the 1936 campaign, but his following remained loyal. He settled in Detroit and was befriended by Henry Ford. Ford financed a series of radio broadcasts for Smith's 1942 Senate race. Smith sought the nomination of Michigan’s Republican Party, winning 100,000 votes and running second in the primary. He credited Ford with revealing the connection between communism and Judaism. “The day came when I embraced the research of Mr. Ford and his associates, and became courageous enough and honest enough and informed enough to use the words: ‘Communism is Jewish.’”

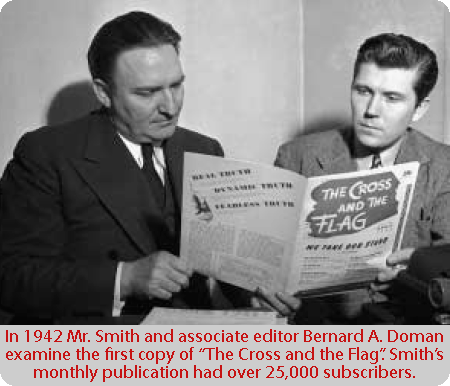

Smith not only continued to speak but also began to write hundreds of tracts, pamphlets, and books, and nearly every word of a monthly magazine, The Cross and the Flag, which he began publishing in 1942 with twenty-five thousand subscribers. His writing, like his speaking, was concise and hard-hitting, identifying and denouncing villains, and praising men of character fighting for the right. His adjective-laden sentences with their hard hitting analogies and humor was hateful to all liberals. He was living in a world controlled by far left villains and jewish conspiracies. A workaholic, he wrote skillfully crafted articles with assembly-line consistency. Also in 1942 he founded the political action group, the Christian Nationalist Crusade.

In 1940 Smith became associated with the America First Committee. It soon became the most powerful isolationist group in the United States. The America First National Committee included Robert E. Wood, John T. Flynn and Charles A. Lindbergh. Supporters of the organization included Gerald L. K. Smith, Burton K. Wheeler, Robert R. McCormick, Hugh Johnson, Robert LaFollette Jr., Amos Pinchot, Hamilton Fish and Gerald Nye. The AFC had four main principles: (1) The United States must build an impregnable defense for America; (2) No foreign power, nor group of powers, can successfully attack a prepared America; (3) American democracy can be preserved only by keeping out of the European War; (4) "And short of war" weakens national defense at home and threatens to involve America in war abroad. The AFC influenced public opinion through publications and speeches and within a year had over 800,000 members. However, the AFC was dissolved four days after the Japanese Air Force attacked Pearl Harbor on 7th December, 1941 which was due to Roosevelt’s threats of trying all the members of the AFC for treason.

Smith barnstormed the nation in the 1940s, crusading against communism, the “Jew-infested” United Nations, and the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and NATO. He moved his headquarters to St. Louis in 1947, to Tulsa in 1949, and to Los Angeles in 1953. He appeared in public infrequently in the late 1950s, but in the 1960s he began constructing what he termed his “Sacred Projects” in the Ozark hamlet of Eureka Springs, Arkansas. A prosperous spa in the 1890s, Eureka Springs was economically dead until Smith began his projects there. He bought a Victorian house called Penn Castle in 1964, renovated it, and made it his summer home. In 1966 he constructed and dedicated the “Christ of the Ozarks,” a seven-story cross-shaped statue of Jesus that is half as tall as the Statue of Liberty and twice the size of the well-known “Christ of the Andes” in South America. It still stands in Eureka Springs, weighs 340 tons; the face is fifteen feet high, and the hands are seven feet long.

Smith’s list of allies was long, but his list of enemies was longer. He called President “Roosenfelt” a traitor. He said, “Practically everybody that goes to church regular, is willing to work hard, and takes a bath once a week is against Roosevelt.” Smith detested Roosevelt’s successor, Harry “Solomon” Truman: “Don’t think for a moment I think Harry Truman was a Communist. He wasn't smart enough.” Dwight D. Eisenhower was a “Swedish Jew,” a dupe of his brother Milton, a general who gave away Eastern Europe to the Russians and “fraternized in drunken brawls with (the Russian general Georgi) Zhukov.” Smith made no distinctions between corrupted leaders whether they were conservatives, liberals, or socialists. They were all enemies of the Republic, the conservative Richard Nixon as well as the liberal Lyndon Johnson. Johnson was “guilty of murder, homosexuality, a wide variety of perversions, thievery, treason, and corruption.”

In 1968 Smith began staging a Passion Play in an amphitheater carved into the side of a mountain outside Eureka Springs. Performed on a four-hundred-foot street of Old Jerusalem, it includes 150 actors and actresses nightly, illuminated by powerful colored spotlights, miming a script broadcast over a stereophonic system. The cast includes live sheep, goats, donkeys, Arabian horses, pigeons, and camels. The two-hour play drew more than 28,000 spectators the first year in a 3,000-seat theater. By 1975 the theater expanded to a capacity of 6,000, and more than 188,000 attended the play, making it the largest outdoor pageant in America. Jews complained that the play was anti-Semitic, but Smith rejoined by calling it “the only presentation of this kind in the world that has not diluted its content to flatter the Christ-hating Jews.”

Smith’s Sacred Projects revived the economy of Eureka Springs, and he became a local hero. The community expanded its restaurants and hotels, and other entrepreneurs moved in. By 1975 Eureka Springs was the leading tourist community in Arkansas, and Smith had bigger plans yet. He planned to construct a replica of the Holy Land, including the Sea of Galilee, the River Jordan, and scenes from the life of Jesus. Visitors could even be baptized in the river. Smith’s new Holy Land, slated to cost $100 million. However, only the Great Wall of Jerusalem had been completed in 1976 when Gerald L. K. Smith died of pneumonia at age seventy-eight.

Smith was buried at the feet of the “Christ of the Ozarks”. His Sacred Projects were his great joy. Through the last four decades of his life he had continued to publish The Cross and the Flag and write thousands of tracts. Even after four decades has past since his death, the far left jew controlled media still attacks this force for truth.

Learn what Dr. Smith knew - More Info

Website and content Copyright © by Dewey H. Tucker - All Rights Reserved.